Text: Friederike Teller | Image: © Sena Karadeniz

You can find the German version of the Interview here

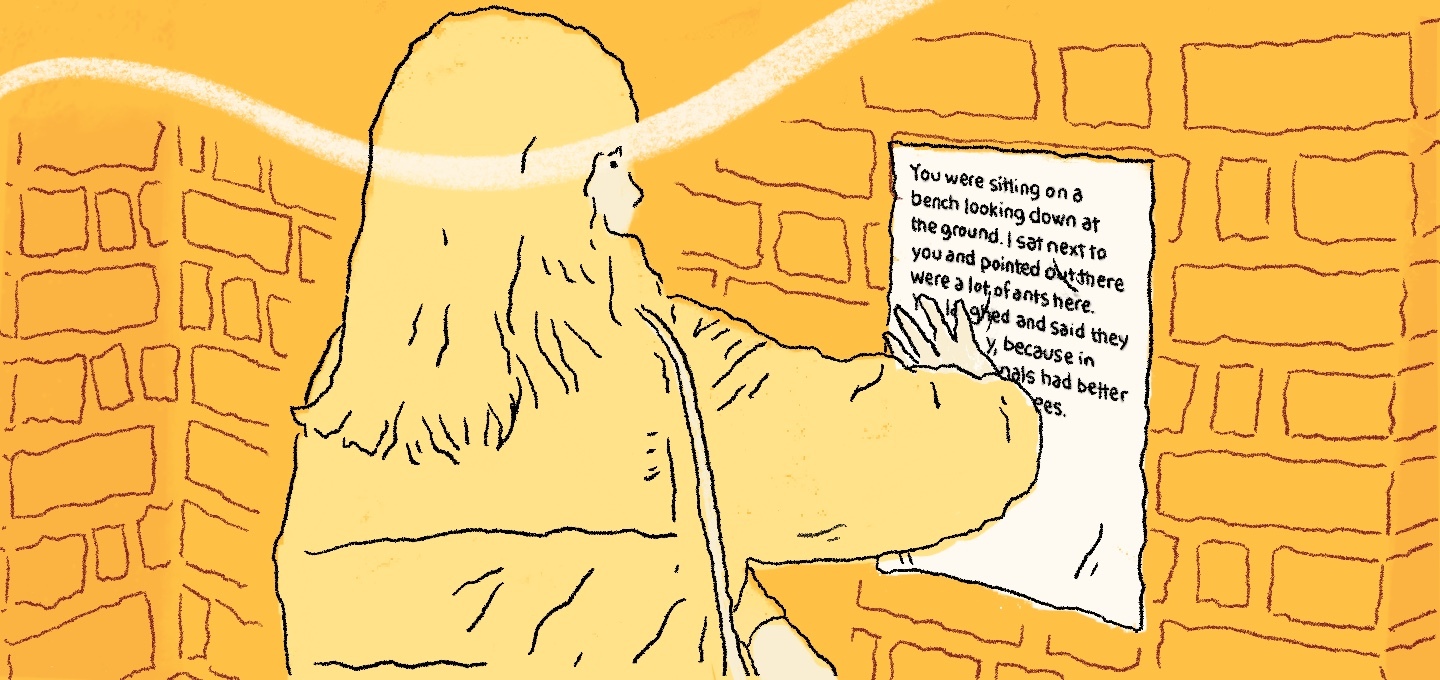

Mathilda Della Torre founded the refugee-volunteer storytelling project conversations from calais. She is a young graphic-designer currently based in London.

You founded the project conversations from calais which collects fragments of conversations between refugees and volunteers from Calais in Northern France. You were trained as a graphic designer. How did you get politically engaged with your design practice?

It wasn’t until I came out of my BA in illustrating when I was starting to get into politics. I worked with the theme of home and how we create a home before, but none of it was directly related to politics or activism. I was really far away from that world.

But then right before starting my masters I wanted to go to Calais. I’m originally French and heard about the situation before. So when I saw that charities were looking for people to help I decided that I would go together with my mom for just 10 days. Obviously I wanted to help but it was more curiosity that brought me there. Not till I came back did I start to think about how design related to politics, activism and change. It sounds clean and efficient now but it was very messy.

conversations from calais features conversations between volunteers and refugees in Calais and posts them publicly. How did you develop the idea ?

British media was portraying Calais in a very negative, racist and discriminatory way. I wanted to help to bridge this gap between what I was seeing and hearing there and what people were seeing here in the UK. I started going through the notes and sketchbooks from my time in Calais. Mostly I had collected conversations that I wanted to remember. I thought a lot about my own perspective too. I’m a volunteer, so this project has to come from the perspective of a volunteer. I’m not a refugee.

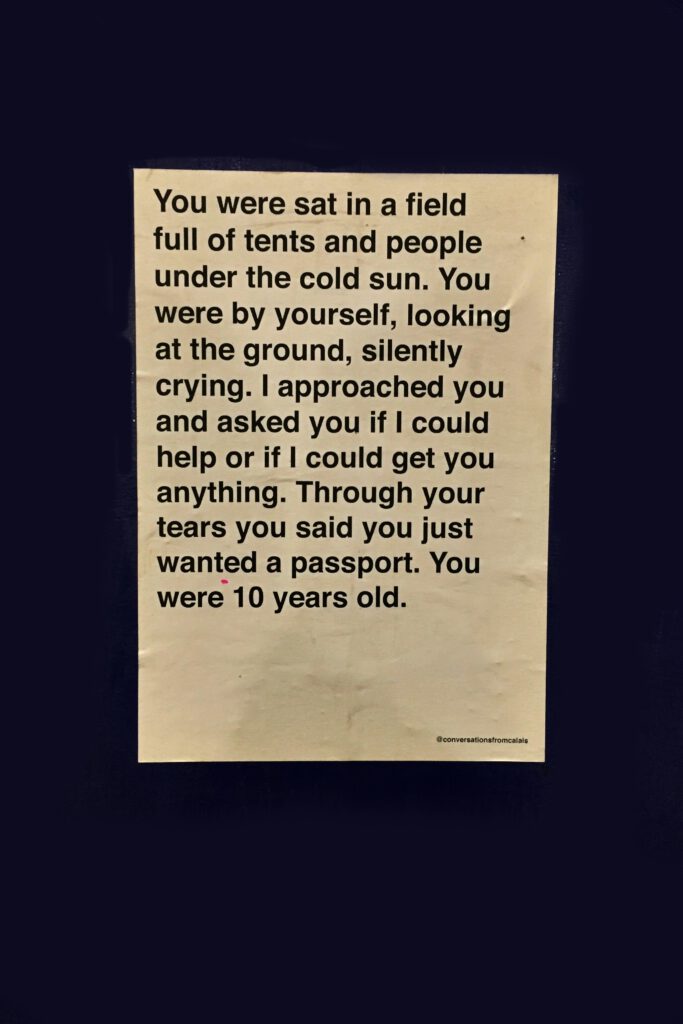

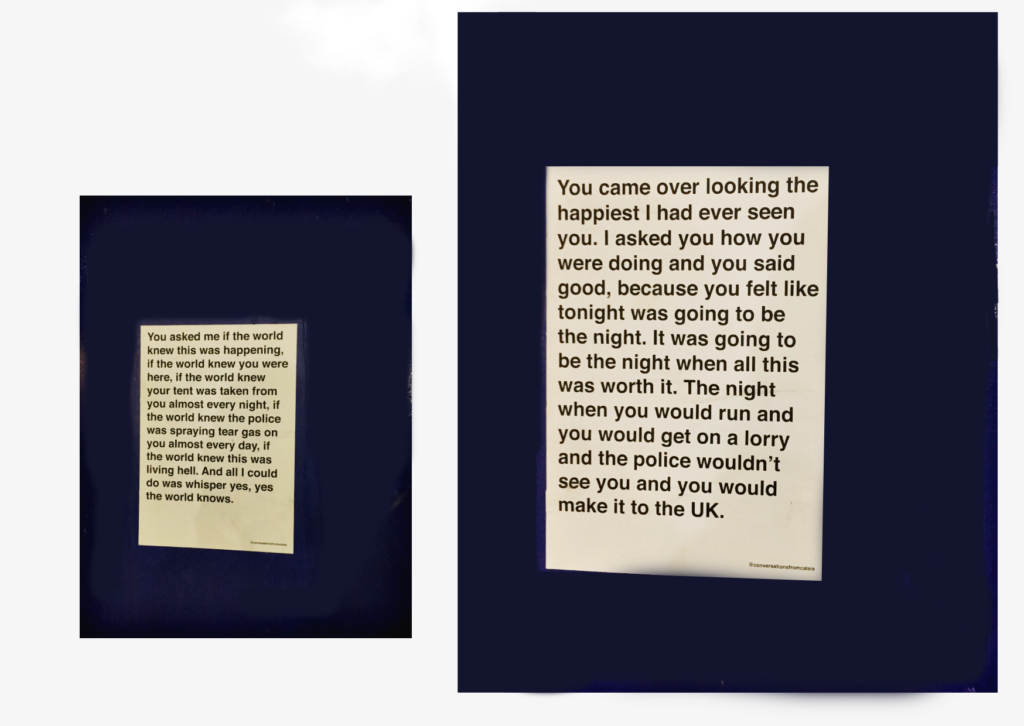

Then I wanted to get these conversations out as fast as possible. I didn’t have time to go to publishers or galleries or journalists, so I thought the easiest would be to just hang them up in the street with glue that I make at home in 10 minutes. Although a lot of people come across the project via Instagram and social media platforms, the project lives on the streets before it lives anywhere else. Every single conversation on our Instagram is pasted in London. That is really important because for me it means that anyone and everyone can hopefully read these conversations and it breaks away these barriers that we have to get through in order to tell a story.

As you said conversations from calais has been pasted in streets all over Europe, been translated into many different languages and was features all in many different media. How did it grow and how did this personally influence your work?

The project grew but that process remained the same: The conversations get submitted by volunteers that have been there. Sometimes I slightly edit them after to shorten them or transform them into the first person perspective, but that’s it. I will continue to paste them as long as people submit them. People wanted to paste the conversations themselves so they have been translated into languages that I don’t speak and they have been posted in cities all over Europe. They are also used in schools or at events. I really like that the project became a resource. I also have got very positive feedback on social media and via emails both by people who made it out of Calais or are volunteers or people that knew nothing about what was happening. I also got emails from people saying, „I’m in Moria, in Paris or in Italy. Can I copy this exact idea,“ but I don’t think it’ll be as effective just to replicate this everywhere because I think we need new ways of showing and highlighting stories. I hope that conversations from calais inspires people to think of multiple ways to bear witness for what they’re living through or what they are witnessing as volunteers.

You narrate the project from the perspective of a volunteer in the speaker position and the refugee as the you. How do you navigate the difficulties of reproducing power-dynamics by portraying the refugee from a ‚white‘ perspective as the ‚other‘ ?

There’s a really big power relationship in any sort of volunteering in the field of migration. Calais especially is a very transitionary camp. It’s where people go to get to the UK so people don’t try and stay there. So that makes the correlations even stronger. For me, the first way of navigating this is that when I am in Calais I’m a volunteer. I am not a designer for ‚conversations from calais‘. I really focus on just doing the tasks I did the first time I was there. Then, when I’m in London I work on the project. This separation is important for me so I don’t force conversations – that I don’t try to get people to tell me things.

The way that I think the project makes sense is to be able to be put in the position of a live volunteer. I hope it helps them to step into someone’s shoes that are more similar to theirs. And then it’s very important to not just reproduce a white gaze and I’ve questioned my work many many many times. I want this project to be a gateway for people to engage with material that has been written, filmed, photographed, created by people’s lived experience. Because I will never be able to tell the refugee story. So, I continue to question how much space I am taking up and I continue to direct people to other initiatives. I think a lot of charities right now are focusing on raising funds which is very important but if we’re not working on advocating and centering voices with lived experiences to help us to take down the systems that are continuing this cycle of refugee issues, then frankly I don’t think that’s enough.

// Mathilda send some resources to further engage with the topic of migration in Europe, which you can find underneath the interview //

The camp in calais, also known as ‚calais jungle’existed between January 2015 and October 2016, when it was demolished by the police. It is estimated that over 9,000 refugees lived there. How has it changed since then and how is the situation now?

Back in 2016 there was a very set camp with loads of people there and a whole community. People rented restaurants, churches, schools and mosques, but all of that was destroyed in 2016. Since I’ve been going it’s always been very small little camps, groups of people that are around Calais in northern France. But police evictions escalated a lot in the past year. The police takes everything that people have, tents, clothes, bags whatever is there and get everyone to move. So, people just end up walking on the highway. The camp in Calais, is not even a camp anymore to be honest.

And then last week the nationality and borders bill went through in the House of Commons in the UK. It has also been called the anti-refugee bill because that’s what it is. It’s not finalized yet but it’s a bill that covers a lot of new laws that will discriminate anyone trying to seek refuge in the UK. It also penalizes people that get to the UK through so called Illegal routes which includes anyone coming from Calais. It’s basically making the UK a place for people to not be able to apply for asylum, to get asylum and finally to stay.

How did the war in Ukraine influenced the situation in Calais and the debate around it?

In a lot of ways the conversation around refugees has changed immensely in the past three weeks because of everything that is happening in Ukraine and in Russia. People realized, that it can happen anywhere and to anyone and that is good. A great first step because it hopefully allows us to feel more empathy for people that are going through it. But people also have been giving excuses for people that are so called civilized and privileged European refugees in contrary to refugees that come from Middle East or North Africa or anywhere else. This is very scary. For example, the mayor of Calais, few weeks ago decided to host Ukraine and refugees in in Calais and hotels so that is something that I had never heard of before. Now is a deciding point for how we are going to move on – are we confirming those discriminatory ideas that people are having unfortunately or are people going to wake up.

***

The Interview was held on April 1, 2022 by Friederike Teller

Recommendations

Hostile – A documentary about the Nationality and Borders bill

Voices from the Jungle – Stories from the Calais Refugee „Jungle“

The Ungrateful Refugee – A book written by Dina Nayeri

Pingback: Zeug:in werden – sai